Defending the Filibuster

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- After years of supporting and defending the filibuster during the Trump administration, Senate Democrats have begun alleging that the filibuster is a racist product of the segregation era.

- The filibuster’s history goes back far earlier than this, and just like every other legislative tactic, it has been used for both good and bad purposes.

- At a time of sharp, even dangerous partisanship, ending the filibuster would ratchet tensions even higher and raise the stakes still further for every federal election.

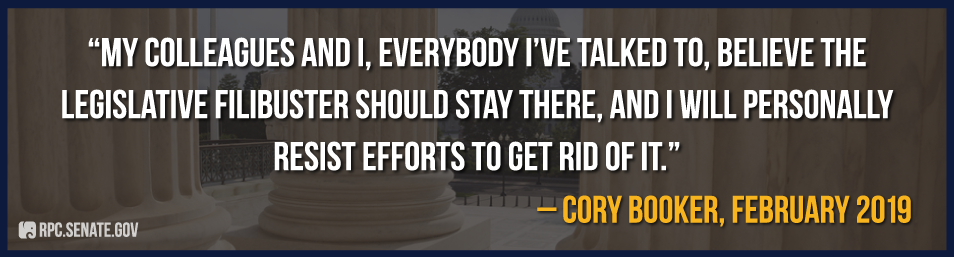

After years of supporting and defending the filibuster when Republicans controlled the Senate and White House, Democrats suddenly claim that the filibuster is a racist relic of the segregation era. The fact that so many Democratic senators have been on both sides of this issue is the first hint that the case against the filibuster is based on convenience rather than conviction, let alone facts.

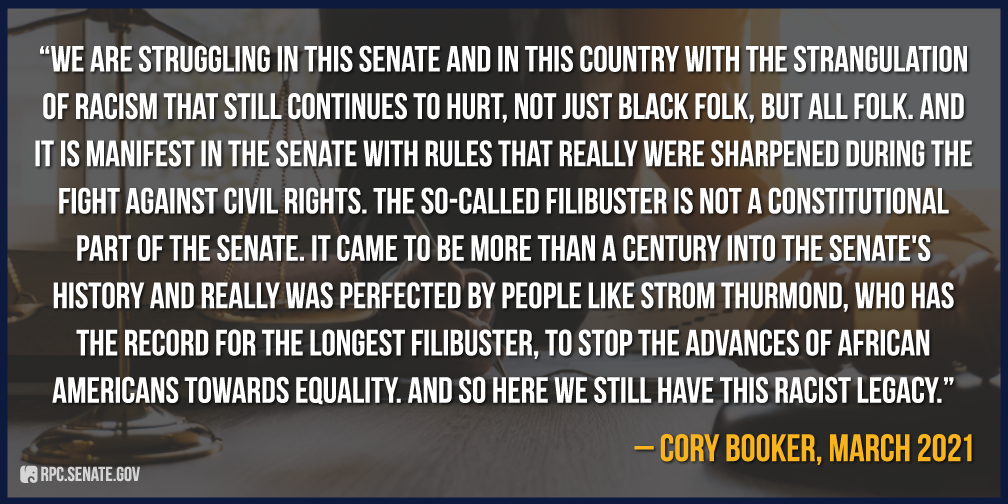

In 2019, when Republicans held the White House and controlled the Senate, Senator Cory Booker was a strong supporter of the filibuster. By 2021 he was downplaying the procedure’s value and saying it was a new, racist innovation. Contrary to the senator’s claims, the filibuster became available for use in 1806 and was first employed in 1837. Neither its creation nor its first use had anything to do with slavery, civil rights, or racism. Like every other legislative maneuver, it has been used for both good and bad things. What matters is whether the need to find more than a bare majority to pass major legislation prevents more bad ideas than good ideas from becoming law.

The Filibuster: Racist or Not Racist, Depending on the Date

History of the Filibuster

The concept of the filibuster goes back even further than its use in the United States, to ancient Rome and Cato the Younger attempting to block Julius Caesar’s power grabs. In U.S. history, the filibuster’s story begins in 1806 when Vice President Aaron Burr reorganized the Senate rules to remove a motion to consider the previous question, creating the possibility of a filibuster. It was not until 1837 that senators actually made the first filibuster. They were trying to stop supporters of Andrew Jackson from rescinding a censure that the Senate had passed against him for withdrawing federal deposits from the Bank of the United States.

The filibuster was by no means a uniquely pro-slavery instrument. It was used by some senators to slow or stop antislavery provisions, but it was used more often in the later part of the 19th century on international matters like the annexation of Hawaii and an extradition treaty with France. The House of Representatives changed its rules in 1842 to remove the possibility of filibuster in that chamber, over the objection of famed abolitionist and civil rights advocate John Quincy Adams. Use of the filibuster against bills relating to American involvement in World War I spurred the creation of the cloture motion in 1917.

More Democratic Flip Flops on the Filibuster

The Filibuster and Civil Rights

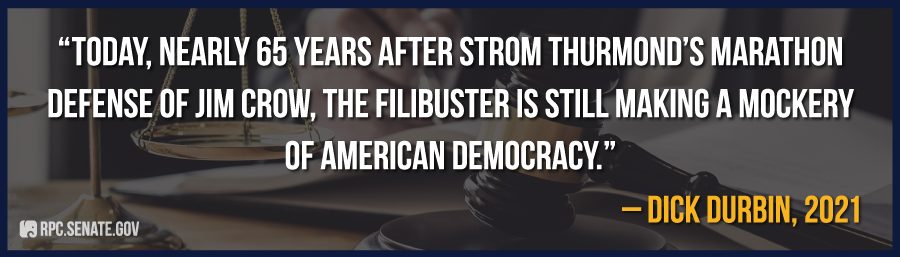

Democrats argue that Senator Strom Thurmond’s unsuccessful filibusters against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1964 prove the need to remove the filibuster in its entirety. The 1957 filibuster ended without even needing a cloture vote. The existence or absence of the filibuster would not have altered the outcome for either law.

Some people argue civil rights legislation would have been passed earlier without a supermajority cloture requirement, but it is highly uncertain that there were previously enough votes for passage. For example, a civil rights bill in 1960 was successfully filibustered, but there were only 42 votes for cloture, and 53 votes against. The bill would probably have fallen short of a majority even without that procedural hurdle.

As with any legislative tool, the filibuster was used on both sides of the civil rights debate. In October 1972, senators introduced three anti-busing bills that were successfully filibustered. In each case, there were more ayes than nays, but not enough ayes to invoke cloture, so the filibuster did alter those outcomes, assuming the senators would have voted the same way on passage as on cloture.

While it is impossible to know every bill stopped by the threat of filibuster, we do know every bill for which a cloture motion was filed. The vast majority had nothing to do with civil rights, even before the use of cloture motions skyrocketed around 1971.

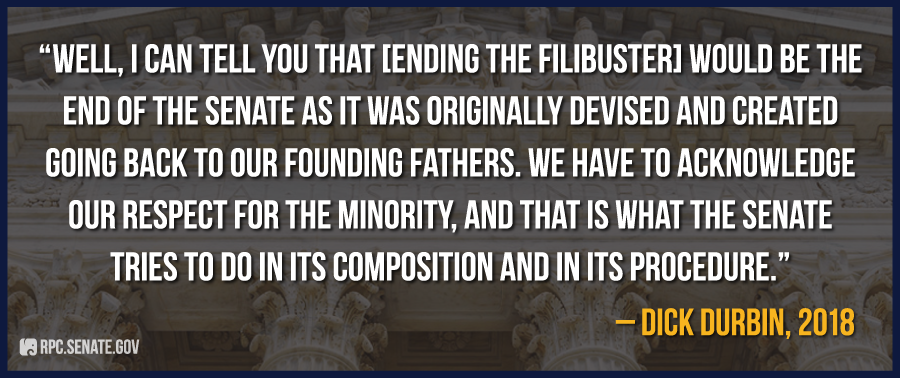

The Filibuster and the Identity of the Senate

Many senators, Republicans and Democrats, have noted that the Senate would not be the Senate without the legislative filibuster. As President Biden said when he was in the Senate, “At its core, the filibuster is not about stopping a nominee or a bill, it's about compromise and moderation.” Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said four years ago that the legislative filibuster is the most important difference between the Senate and the House.

Senator Jon Tester specifically noted his opposition to eliminating the procedure: “I don’t want to see the Senate become the House.” The difference between the chambers was famously attributed to George Washington, that the Senate is the saucer used to cool House legislation.

We all know what will happen without the saucer: exactly the sort of wild swings in policy that the founders warned against at length. In Federalist No. 62, Alexander Hamilton wrote about the importance of the Senate in keeping the country’s course steady: “It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow.”

Observers of any political stripe looking through the list of cloture motions will find some filibustered bills they like, and some they dislike. The potential for bad bills to pass without the filibuster is obvious. Perhaps less obvious: without the filibuster, at a time of razor-thin margins in the House and Senate, how much confidence can Democrats have that the partisan laws they enact today will not be repealed in four years?

Next Article Previous Article